The wars with the Etruscans went on, and chiefly with the city of Veii, which stood on a hill twelve miles from Rome, and was altogether thirty years at war with it. At last the Romans made up their minds that, instead of going home every harvest-time to gather in their crops, they must watch the city constantly till they could take it, and thus, as the besiegers were unable to do their own work, pay was raised for them to enable them to get it done, and this was the beginning of paying armies.

The siege of Veii lasted ten years, and during the last the Alban lake filled to an unusual height, although the summer was very dry. One of the Veian soldiers cried out to the Romans half in jest, "You will never take Veii till the Alban lake is dry." It turned out that there was an old tradition that Veii should fall when the lake was drained. On this the senate sent orders to have canals dug to carry the waters to the sea, and these still remain. Still Veii held out, and to finish the war a dictator was appointed, Marcus Furius Camillus, who chose for his second in command a man of one of the most virtuous families in Rome, as their surname testified, Publius Cornelius, called Scipio, or the Staff, because either he or one of his forefathers had been the staff of his father's old age. Camillus took the city by assault, with an immense quantity of spoil, which was divided among the soldiers.

Camillus in his pride took to himself at his triumph honors that had hitherto only been paid to the gods. He had his face painted with vermilion and his car drawn by milk-white horses. This shocked the people, and he gave greater offence by declaring that he had vowed a tenth part of the spoil to Apollo, but had forgotten it in the division of the plunder, and now must take it again. The soldiers would not consent, but lest the god should be angry with them, it was resolved to send a gold vase to his oracle at Delphi. All the women of Rome brought their jewels, and the senate rewarded them by a decree that funeral speeches might be made over their graves as over those of men, and likewise that they might be driven in chariots to the public games.

Camillus commanded in another war with the Falisci, also an Etruscan race, and laid siege to their city. The sons of almost all the chief families were in charge of a sort of schoolmaster, who taught them both reading and all kinds of exercises. One day this man, pretending to take the boys out walking, led them all into the enemy's camp, to the tent of Camillus, where he told that he brought them all, and with them the place, since the Romans had only to threaten their lives to make their fathers deliver up the city. Camillus, however, was so shocked at such perfidy, that he immediately bade the lictors strip the fellow instantly, and give the boys rods with which to scourge him back into the town. Their fathers were so grateful that they made peace at once, and about the same time the Æqui were also conquered; and the commons and open lands belonging to Veii being divided, so that each Roman freeman had six acres, the plebeians were contented for the time.

The truth seems to have been that these Etruscan nations were weakened by a great new nation coming on them from the North. They were what the Romans called Galli or Gauls, one of the great races of the old stock which has always been finding its way westward into Europe, and they had their home north of the Alps, but they were always pressing on and on, and had long since made settlements in northern Italy. They were in clans, each obedient to one chief as a father, and joining together in one brotherhood. They had lands to which whole families had a common right, and when their numbers outgrew what the land could maintain, the bolder ones would set off with their wives, children, and cattle to find new homes. The Greeks and Romans themselves had begun first in the same way, and their tribes, and the claims of all to the common land, were the remains of the old way; but they had been settled in cities so long that this had been forgotten, and they were very different people from the wild men who spoke what we call Welsh, and wore checked tartan trews and plaids, with gold collars round their necks, round shields, huge broadswords, and their red or black hair long and shaggy. The Romans knew little or nothing about what passed beyond their own Apennines, and went on with their own quarrels. Camillus was accused of having taken more than his proper share of the spoil of Veii, in especial a brass door from a temple. His friends offered to pay any fine that might be laid on him, but he was too proud to stand his trial, and chose rather to leave Rome. As he passed the gates, he turned round and called upon the gods to bring Rome to speedy repentance for having driven him away.

Even then the Gauls were in the midst of a war with Clusium, the city of Porsena, and the inhabitants sent to beg the help of the Romans, and the senate sent three young brothers of the Fabian family to try to arrange matters. They met the Gaulish Bran or chief, whom Latin authors call Brennus, and asked him what was his quarrel with Clusium or his right to any part of Etruria. Brennus answered that his right was his sword, and that all things belonged to the brave, and that his quarrel with the men of Clusium was, that though they had more land than they could till, they would not yield him any. As to the Romans, they had robbed their neighbors already, and had no right to find fault.

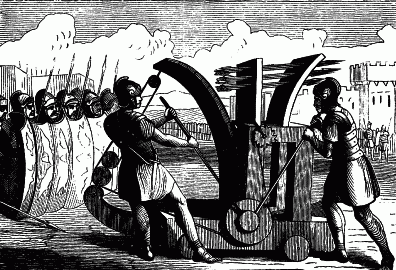

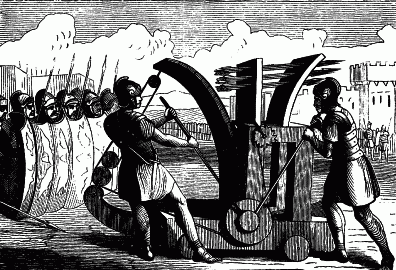

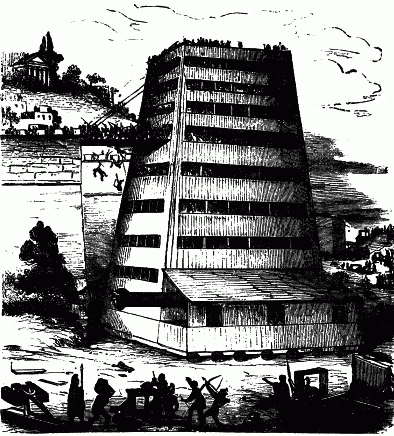

This put the Fabian brothers in a rage, and they forgot the caution of their family, as well as those rules of all nations which forbid an ambassador to fight, and also forbid his person to be touched by the enemy; and when the men of Clusium made an attack on the Gauls they joined in the attack, and Quintus, the eldest brother, slew one of the chiefs. Brennus, wild as he was, knew these laws of nations, and in great anger broke up his siege of Clusium, and, marching towards Rome, demanded that the Fabii should be given up to him. Instead of this, the Romans made them all three military tribunes, and as the Gauls came nearer the whole army marched out to meet them in such haste that they did not wait to sacrifice to the gods nor consult the omens. The tribunes were all young and hot-headed, and they despised the Gauls; so out they went to attack them on the banks of the Allia, only seven and a-half miles from Rome. A most terrible defeat they had; many fell in the field, many were killed in the flight, others were drowned in trying to swim the Tiber, others scattered to Veii and the other cities, and a few, horror-stricken and wet through, rushed into Rome with the sad tidings. There were not men enough left to defend the walls! The enemy would instantly be upon them! The only place strong enough to keep them out was the Capitol, and that would only hold a few people within it! So there was nothing for it but flight. The braver, stronger men shut themselves up in the Capitol; all the rest, with the women and children, put their most precious goods into carts and left the city. The Vestal Virgins carried the sacred fire, and were plodding along in the heat, when a plebeian named Albinus saw their state, helped them into his cart, and took them to the city of Cumæ, where they found shelter in a temple. And so Rome was left to the enemy.