In the year 332, just when Alexander the Great was making his conquests in the East, his uncle Alexander, king of Epirus, brother to his mother Olympius, came to Italy, where there were so many Grecian citizens south of the Samnites that the foot of Italy was called Magna Græcia, or Greater Greece. He attacked the Samnites, and the Romans were not sorry to see them weakened, and made an alliance with him. He stayed in Italy about six years, and was then killed.

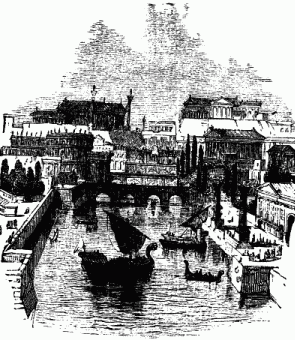

To overthrow the Samnites was the great object of Rome at this time, and for this purpose they offered their protection and alliance to all the cities that stood in dread of that people. One of the cities was founded by men from the isle of Euboea, who called it Neapolis, or the New City, to distinguish it from the old town near at hand, which they called Palæopolis, or the Old City. The elder city held out against the Romans, but was easily overpowered, while the new one submitted to Rome; but these southern people were very shallow and fickle, and little to be depended on, as they often changed sides between the Romans and Samnites. In the midst of the siege of Palæopolis, the year of the consulate came to an end, but the Senate, while causing two consuls as usual to be elected, at home, would not recall Publilius Philo from the siege, and therefore appointed him proconsul there. This was in 326, and was the beginning of the custom of sending the ex-consul as proconsul to command the armies or govern the provinces at a distance from home.

In 320, the consul falling sick, a dictator was appointed, Lucius Papirius Cursor, one of the most stern and severe men in Rome. He was obliged by some religious ceremony to return to Rome for a time, and he forbade his lieutenant, Quintus Fabius Rullianus, to venture a battle in his absence. But so good an opportunity offered that Fabius attacked the enemy, beat them, and killed 20,000 men. Then selfishly unwilling to have the spoils he had won carried in the dictator's triumph, he burnt them all. Papirius arrived in great anger, and sentenced him to death for his disobedience; but while the lictors were stripping him, he contrived to escape from their hands among the soldiers, who closed on him, so that he was able to get to Rome, where his father called the Senate together, and they showed themselves so resolved to save his life that Papirius was forced to pardon him, though not without reproaching the Romans for having fallen from the stern justice of Brutus and Manlius.

Two years later the two consuls, Titus Veturius and Spurius Posthumius, were marching into Campania, when the Samnite commander, Pontius Herennius, sent forth people disguised as shepherds to entice them into a narrow mountain pass near the city of Candium, shut in by thick woods, leading into a hollow curved valley, with thick brushwood on all sides, and only one way out, which the Samnites blocked up with trunks of trees. As soon as the Romans were within this place the other end was blocked in the same way, and thus they were all closed up at the mercy of their enemies.

What was to be done with them? asked the Samnites; and they went to consult old Herennius, the father of Pontius, the wisest man in the nation. "Open the way and let them all go free," he said.

"What! without gaining any advantage?"

"Then kill them all."

He was asked to explain such extraordinary advice. He said that to release them generously would be to make them friends and allies for ever; but if the war was to go on, the best thing for Samnium would be to destroy such a number of enemies at a blow. But the Samnites could not resolve upon either plan; so they took a middle course, the worst of all, since it only made the Romans furious without weakening them. They were made to take off all their armor and lay down their weapons, and thus to pass out under the yoke, namely, three spears set up like a doorway. The consuls, after agreeing to a disgraceful peace, had to go first, wearing only their undermost garment, then all the rest, two and two, and if any one of them gave an angry look, he was immediately knocked down and killed. They went on in silence into Campania, where, when night came on, they all threw themselves, half-naked, silent, and hungry upon the grass. The people of Capua came out to help them, and brought them food and clothing, trying to do them all honor and comfort them, but they would neither look up nor speak. And thus they went on to Rome, where everybody had put on mourning, and all the ladies went without their jewels, and the shops in the Forum were closed. The unhappy men stole into their houses at night one by one, and the consuls would not resume their office, but two were appointed to serve instead for the rest of the year.

Revenge was all that was thought of, but the difficulty was the peace to which the consuls had sworn. Posthumius said that if it was disavowed by the Senate, he, who had been driven to make it, must be given back to the Samnites. So, with his hands tied, he was taken back to the Samnite camp by a herald and delivered over; but at that moment Posthumius gave the herald a kick, crying out, "I am now a Samnite, and have insulted you, a Roman herald. This is a just cause of war." Pontius and the Samnites were very angry, and they said it was an unworthy trick; but they did not prevent Posthumius from going safely back to the Romans, who considered him to have quite retrieved his honor.

A battle was fought, in which Pontius and 7000 men were forced to lay down their arms and pass under the yoke in their turn. The struggle between these two fierce nations lasted altogether seventy years, and the Romans had many defeats. They had other wars at the same time. They never subdued Etruria, and in the battle of Sentinum, fought with the Gauls, the consul Decius Mus, devoted himself exactly as his father had done at Vesuvius, and by his death won the victory.

The Samnite wars may be considered as ending in 290, when the chief general of Samnium, Pontius Telesimus, was made prisoner and put to death at Rome. The lands in the open country were quite subdued, but many Samnites still lived in the fastnesses of the Apennines in the south, which have ever since been the haunt of wild untamed men.