After the death of Massinissa, king of Numidia, the ally of the Romans, there were disputes among his grandsons, and Jugurtha, whom they held to have the least right, obtained the kingdom. The commander of the army sent against him was Caius Marius, who had risen from being a free Roman peasant in the village of Arpinum, but serving under Scipio Æmilianus, had shown such ability, that when some one was wondering where they would find the equal of Scipio when he was gone, that general touched the shoulder of his young officer and said, "Possibly here."

Rough soldier as he always was, he married Julia, of the high family of the Cæsars, who were said to be descended from Æneas; and though he was much disliked by the Senate, he always carried the people with him. When he received the province of Numidia, instead of, as every one had done before, forming his army only of Roman citizens, he offered to enlist whoever would, and thus filled his ranks with all sorts of wild and desperate men, whom he could indeed train to fight, but who had none of the old feeling for honor or the state, and this in the end made a great change in Rome.

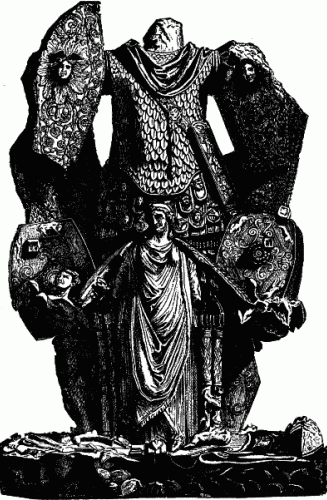

Jugurtha maintained a wild war in the deserts of Africa with Marius, but at last he was betrayed to the Romans by his friend Bocchus, another Moorish king, and Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Marius' lieutenant, was sent to receive him—a transaction which Sulla commemorated on a signet ring which he always wore. Poor Jugurtha was kept two years to appear at the triumph, where he walked in chains, and then was thrown alive into the dungeon under the Capitol, where he took six days to die of cold and hunger.

Marius was elected consul for the second time even before he had quite come home from Africa, for it was a time of great danger. Two fierce and terrible tribes, whom the Romans called Cimbri and Teutones, and who were but the vanguard of the swarms who would overwhelm them six centuries later, had come down through Germany to the settled countries belonging to Rome, especially the lands round the old Greek settlements in Gaul, which had fallen of course into the hands of the Romans, and were full of beautiful rich cities, with houses and gardens round them. The Province, as the Romans called it, would have been grand plundering ground for these savages, and Marius established himself in a camp on the banks of the Rhone to protect it, cutting a canal to bring his provisions from the sea, which still remains. While he was thus engaged, he was a fourth time elected consul.

The enemy began to move. The Cimbri meant to march eastward round the Alps, and pour through the Tyrol into Italy; the Teutones to go by the West, fighting Marius on the way. But he would not come out of his camp on the Rhone, though the Teutones, as they passed, shouted to ask the Roman soldiers what messages they had to send to their wives in Italy.

When they had all passed, he came out of his camp and followed them as far as Aquæ Sextiæ, now called Aix, where one of the most terrible battles the world ever saw was fought. These people were a whole tribe—wives, children, and everything they had with them—and to be defeated was utter and absolute ruin. A great enclosure was made with their carts and wagons, whence the women threw arrows and darts to help the men; and when, after three days of hard fighting, all hope was over, they set fire to the enclosure and killed their children and themselves. The whole swarm was destroyed. Marius marched away, and no one was left to bury the dead, so that the spot was called the Putrid Fields, and is still known as Les Pourrieres.

While Marius was offering up the spoil, tidings came that he was a fifth time chosen consul; but he had to hasten into Italy, for the other consul, Catulus, could not stand before the Cimbri, and Marius met him on the Po retreating from them. The Cimbri demanded lands in Italy for themselves and their allies the Teutones. "The Teutones have all the ground they will ever want, on the other side the Alps," said Marius; and a terrible battle followed, in which the Cimbri were as entirely cut off as their allies had been.

Marius was made consul a sixth time. As a reward to the brave soldiers who had fought under him, he made one thousand of them, who came from the city of Camerinum, Roman citizens, and this the patricians disliked greatly. His excuse was, "The din of arms drowned the voice of the law;" but the new citizens were provided for by lands in the Province, which the Romans said the Gauls had lost to the Teutones and they had reconquered. It was very hard on the Gauls, but that was the last thing a Roman cared about.

The Italians, however, were all crying out for the rights of Romans, and the more far-sighted among the Romans would, like Caius Gracchus, have granted them. Marcus Livius Drusus did his best for them; he was a good man, wise and frank-hearted. When he was having a house built, and the plan was shown him which would make it impossible for any one to see into it, he said, "Rather build one where my fellow-countrymen may see all I do." He was very much loved, and when he was ill, prayers were offered at the temples for his recovery; but no sooner did he take up the cause of the Italians than all the patricians hated him bitterly. "Rome for the Romans," was their watchword. Drusus was one day entertaining an Italian gentleman, when his little nephew, Marcus Porcius Cato, a descendant of the old censor, and bred in stern patrician views, was playing about the room. The Italian merrily asked him to favor his cause. "No," said the boy. He was offered toys and cakes if he would change his mind, but he still refused; he was threatened, and at last he was held by one leg out of the window—all without shaking his resolution for a moment; and this constancy he carried with him through life.

People's minds grew embittered, and Drusus was murdered in the street, crying as he fell, "When will Rome find so good a citizen!" After this, the Italians took up arms, and what was called the Social War began. Marius had no high command, being probably too much connected with the enemy. Some of the Italian tribes held with Rome, and these were rewarded with the citizenship; and after all, though the consul Lucius Julius Cæsar, brother-in-law to Marius, gained some victories, the revolt was so widespread, that the Senate felt it wisest, on the first sign of peace, to offer citizenship to such Italians as would come within sixty days to claim it. Citizenship brought a man under Roman law, freed him from taxation, and gave him many advantages and openings to a rise in life. But he could only give his vote at Rome, and only there receive the distribution of corn, and he further became liable to be called out to serve in a legion, so that the benefit was not so great as at first appeared, and no very large numbers of Italians came to apply for it.