All the time these struggles were going on between the patricians and the plebeians at home, there were wars with the neighboring tribes, the Volscians, the Veians, the Latins, and the Etruscans. Every spring the fighting men went out, attacked their neighbors, drove off their cattle, and tried to take some town; then fought a battle, and went home to reap the harvest, gather the grapes and olives in the autumn, and attend to public business and vote for the magistrates in the winter. They were small wars, but famous men fought in them. In a war against the Volscians, when Cominius was consul, he was besieging a city called Corioli, when news came that the men of Antium were marching against him, and in their first attack on the walls the Romans were beaten off, but a gallant young patrician, descended from the king Ancus Marcius, Caius Marcius by name, rallied them and led them back with such spirit that the place was taken before the hostile army came up; then he fought among the foremost and gained the victory. When he was brought to the consul's tent covered with wounds, Cominius did all he could to show his gratitude—set on the young man's head the crown of victory, gave him the surname of Coriolanus in honor of his exploits, and granted him the tenth part of the spoil of ten prisoners. Of them, however, Coriolanus only accepted one, an old friend of the family, whom he set at liberty at once. Afterwards, when there was a great famine in Rome, Coriolanus led an expedition to Antium, and brought away quantities of corn and cattle, which he distributed freely, keeping none for himself.

But though he was so free of hand, Coriolanus was a proud, shy man, who would not make friends with the plebeians, and whom the tribunes hated as much as he despised them. He was elected consul, and the tribunes refused to permit him to become one; and when a shipload of wheat arrived from Sicily, there was a fierce quarrel as to how it should be distributed. The tribunes impeached him before the people for withholding it from them, and by the vote of a large number of citizens he was banished from Roman lands. His anger was great, but quiet. He went without a word away from the Forum to his house, where he took leave of his mother Veturia, his wife Volumnia, and his little children, and then went and placed himself by the hearth of Tullus the Volscian chief, in whose army he meant to fight to revenge himself upon his countrymen.

Together they advanced upon the Roman territory, and after ravaging the country threatened to besiege Rome. Men of rank came out and entreated him to give up this wicked and cruel vengeance, and to have pity on his friends and native city; but he answered that the Volscians were now his nation, and nothing would move him. At last, however, all the women of Rome came forth, headed by his mother Veturia and his wife Volumnia, each with a little child, and Veturia entreated and commanded her son in the most touching manner to change his purpose and cease to ruin his country, begging him, if he meant to destroy Rome, to begin by slaying her. She threw herself at his feet as she spoke, and his hard spirit gave way.

"Ah! mother, what is it you do?" he cried as he lifted her up. "Thou hast saved Rome, but lost thy son."

And so it proved, for when he had broken up his camp and returned to the Volscian territory till the senate should recall him as they proceeded, Tullus, angry and disappointed, stirred up a tumult, and he was killed by the people before he could be sent for to Rome. A temple to "Women's Good Speed" was raised on the spot where Veturia knelt to him.

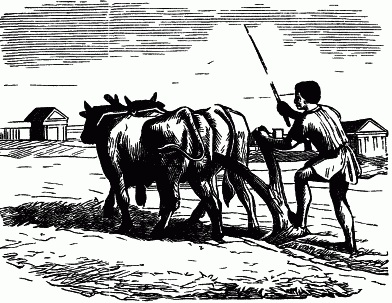

Another very proud patrician family was the Quinctian. The father, Lucius Quinctius, was called Cincinnatus, from his long flowing curls of hair. He was the ablest man among the Romans, but stern and grave, and his eldest son Kæso was charged by the tribunes with a murder and fled the country. Soon after there was a great inroad of the Æqui and Volscians, and the Romans found themselves in great danger. They saw no one could save them but Cincinnatus, so they met in haste and chose him Dictator, though he was not present. Messengers were sent to his little farm on the Tiber, and there they found him holding the stilts of the plough. When they told their errand, he turned to his wife, who was helping him, and said, "Racilia, fetch me my toga;" then he washed his face and hands, and was saluted as Dictator. A boat was ready to take him to Rome, and as he landed, he was met by the four-and-twenty lictors belonging to the two consuls and escorted to his dwelling. In the morning he named as general of the cavalry Lucius Tarquitius, a brave old patrician who had become too poor even to keep a horse. Marching out at the head of all the men who could bear arms, he thoroughly routed the Æqui, and then resigned his dictatorship at the end of sixteen days. Nor would he accept any of the spoil, but went back to his plough, his only reward being that his son was forgiven and recalled from banishment.

These are the grand old stories that came down from old time, but how much is true no one can tell, and there is reason to think that, though the leaders like Cincinnatus and Coriolanus might be brave, the Romans were really pressed hard by the Volscians and Æqui, and lost a good deal of ground, though they were too proud to own it. No wonder, while the two orders of the state were always pulling different ways. However, the tribune Icilius succeeded in the year 454 in getting the Aventine Hill granted to the plebeians; and they had another champion called Lucius Sicinius Dentatus, who was so brave that he was called the Roman Achilles. He had received no less than forty-five wounds in different fights before he was fifty-eight years old, and had had fourteen civic crowns. For the Romans gave an oak-leaf wreath, which they called a civic crown, to a man who saved the life of a fellow-citizen, and a mural crown to him who first scaled the walls of a besieged city. And when a consul had gained a great victory, he had what was called a triumph. He was drawn in his chariot into the city, his victorious troops marching before him with their spears waving with laurel boughs, a wreath of laurel was on his head, his little children sat with him in the chariot, and the spoil of the enemy was carried along. All the people decked their houses and came forth rejoicing in holiday array, while he proceeded to the Capitol to sacrifice an ox to Jupiter there. His chief prisoners walked behind his car in chains, and at the moment of his sacrifice they were taken to a cell below the Capitol and there put to death, for the Roman was cruel in his joy. Nothing was more desired than such a triumph; but such was often the hatred between the plebeians and the patricians, that sometimes the plebeian army would stop short in the middle of a victorious campaign to hinder their consul from having a triumph. Even Sicinius is said once to have acted thus, and it began to be plain that Rome must fall if it continued to be thus divided against itself.