The Religion of the later Babylonians differed in so few respects from that of the early Chaldaeans, their predecessors in the same country, that it will be unnecessary to detain the reader with many observations on the subject. The same gods were worshipped in the same temples and with the same rites—the same cosmogony was taught and held—the same symbols were objects of religious regard—even the very dress of the priests was maintained unaltered; and, could Urukh or Chedorlaomer have risen from the grave and revisited the shrines wherein they sacrificed fourteen centuries earlier, they would have found but little to distinguish the ceremonies of their own day from those in vogue under the successors of Nabopolassar. Some additional splendor in the buildings, the idols, and perhaps the offerings, some increased use of music as a part of the ceremonial, some advance of corruption with respect to priestly impostures and popular religious customs might probably have been noticed; but otherwise the religion of Nabonidus and Belshazzar was that of Urukh and Ilgi, alike in the objects and the mode of worship, in the theological notions entertained and the ceremonial observances taught and practised.

The identity of the gods worshipped during the entire period is sufficiently proved by the repair and restoration of the ancient temples under Nebuchadnezzar, and their re-dedication (as a general rule) to the same deities. It appears also from the names of the later kings and nobles, which embrace among their elements the old divine appellations. Still, together with this general uniformity, we seem to see a certain amount of fluctuation—a sort of fashion in the religion, whereby particular gods were at different times exalted to a higher rank in the Pantheon, and were sometimes even confounded with other deities commonly regarded as wholly distinct from them. Thus Nebuchadnezzar devoted himself in an especial way to Merodach, and not only assigned him titles of honor which implied his supremacy over all the remaining gods, but even identified him with the great Bel, the ancient tutelary god of the capital. Nabonidus, on the other hand, seems to have restored Bel to his old position, re-establishing the distinction between him and Merodach, and preferring to devote himself to the former.

A similar confusion occurs between the goddesses Beltis and Nana or Ishtar, though this is not peculiar to the later kingdom. It may perhaps be suspected from such instances of connection and quasi-convertibility, that an esoteric doctrine, known to the priests and communicated by them to the kings, taught the real identity of the several gods and goddesses, who may have been understood by the better instructed to represent, not distinct and separate beings, but the several phases of the Divine Nature. Ancient polytheism had, it may be surmised, to a great extent this origin, the various names and titles of the Supreme, which designated His different attributes or the different spheres of His operation, coming by degrees to be misunderstood, and to pass, first with the vulgar, and at last with all but the most enlightened, for the appellations of a number of gods.

The chief objects of Babylonian worship were Bel, Merodach, and Nebo. Nebo, the special deity of Borsippa, seems to have been regarded as a sort of powerful patron-saint under whose protection it was important to place individuals. During the period of the later kingdom, no divine element is so common in names. Of the seven kings who form the entire list, three certainly, four probably, had appellations composed with it. The usage extended from the royal house to the courtiers; and such names as Nebu-zar-adan, Samgar-Nebo, and Nebushazban, show the respect which the upper class of citizens paid to this god. It may even be suspected that when Nebuchadnezzar's Master of the Eunuchs had to give Babylonian names to the young Jewish princes whom he was educating, he designed to secure for one of them this powerful patron, and consequently called him Abed-Nebo—the servant of Nebo—a name which the later Jews, either disdaining or not understanding, have corrupted into the Abed-nogo of the existing text.

Another god held in peculiar honor by the Babylonians was Nergal. Worshipped at Cutha as the tutelary divinity of the town, he was also held in repute by the people generally. No name is more common on the cylinder seals. It is sometimes, though not often, an element in the names of men, as in "Nergal-shar-ezer, the Eab-mag," and (if he be a different person) in Neriglissar, the king.

Altogether, there was a strong local element in the religion of the Babylonians. Bel and Merodach were in a peculiar way the gods of Babylon, Nebo of Borsippa, Nergal of Cutha, the Moon of Ur or Hur, Beltis of Niffer, Hea or Hoa of Hit, Ana of Erech, the Sun of Sippara. Without being exclusively honored at a single site, the deities in question held the foremost place each in his own town. There especially was worship offered to them; there was the most magnificent of their shrines. Out of his own city a god was not greatly respected, unless by those who regarded him as their special personal protector.

The Babylonians worshipped their gods indirectly, through images. Each shrine had at least one idol, which was held in the most pious reverence, and was in the minds of the vulgar identified with the god. It seems to have been believed by some that the actual idol ate and drank the offerings. Others distinguished between the idol and the god, regarding the latter as only occasionally visiting the shrine where he was worshipped. Even these last, however, held gross anthropomorphic views, since they considered the god to descend from heaven in order to hold commerce with the chief priestess. Such notions were encouraged by the priests, who furnished the inner shrine in the temple of Bel with a magnificent couch and a golden table, and made the principal priestess pass the night in the shrine on certain occasions.

The images of the gods were of various materials. Some were of wood, others of stone, others again of metal; and these last were either solid or plated. The metals employed were gold, silver, brass, or rather bronze, and iron. Occasionally the metal was laid over a clay model. Sometimes images of one metal were overlaid with plates of another, as was the case with one of the great images of Bel, which was originally of silver but was coated with gold by Nebuchadnezzar.

The worship of the Babylonians appears to have been conducted with much pomp and magnificence. A description has been already given of their temples. Attached to these imposing structures was, in every case, a body of priests; to whom the conduct of the ceremonies and the custody of the treasures were intrusted. The priests were married, and lived with their wives and children, either in the sacred structure itself, or in its immediate neighborhood. They were supported either by lands belonging to the temple, or by the offerings of the faithful. These consisted in general of animals, chiefly oxen and goats; but other valuables were no doubt received when tendered. The priest always intervened between the worshipper and the deities, presenting him to them and interceding with uplifted hands on his behalf.

In the temple of Bel at Babylon, and probably in most of the other temples both there and elsewhere throughout the country, a great festival was celebrated once in the course of each year. We know little of the ceremonies with which these festivals were accompanied; but we may presume from the analogy of other nations that there were magnificent processions on these occasions, accompanied probably with music and dancing. The images of the gods were perhaps exhibited either on frames or on sacred vehicles. Numerous victims were sacrificed; and at Babylon it was customary to burn on the great altar in the precinct of Bel a thousand talents' weight of frankincense. The priests no doubt wore their most splendid dresses; the multitude was in holiday costume; the city was given up to merry-making. Everywhere banquets were held. In the palace the king entertained his lords; in private houses there was dancing and revelling. Wine was freely drunk; passion Was excited; and the day, it must be feared, too often terminated in wild orgies, wherein the sanctions of religion were claimed for the free indulgence of the worst sensual appetites. In the temples of one deity excesses of this description, instead of being confined to rare occasions, seem to have been of every-day occurrence. Each woman was required once in her life to visit a shrine of Beltis, and there remain till some stranger cast money in her lap and took her away with him. Herodotus, who seems to have visited the disgraceful scene, describes it as follows. "Many women of the wealthier sort, who are too proud to mix with the others, drive in covered carriages to the precinct, followed by a goodly train of attendants, and there take their station. But the larger number seat themselves within the holy inclosure with wreaths of string about their heads—and here there is always a great crowd, some coming and others going. Lines of cord mark out paths in all directions among the woman; and the strangers pass along them to make their choice. A women who has once taken her seat is not allowed to return home till one of the strangers throws a silver coin into her lap, and takes her with him beyond the holy ground. When he throws the coin, he says these words—'The goddess Mylitta (Beltis) prosper thee.' The silver coin may be of any size; it cannot be refused; for that is forbidden by the law, since once thrown it is sacred. The woman goes with the first man who throws her money, and rejects no one. When she has gone with him, and so satisfied the goddess, she returns home; and from that time forth no gift, however great, will prevail with her. Such of the women as are tall and beautiful are soon released; but others, who are ugly, have to stay a long time before they can fulfil the law. Some have even waited three or four years in the precinct." The demoralizing tendency of this religious prostitution can scarcely be overrated.

Notions of legal cleanliness and uncleanliness, akin to those prevalent among the Jews, are found to some extent in the religious system of the Babylonians. The consummation of the marriage rite made both the man and the woman impure, as did every subsequent act of the same kind. The impurity was communicated to any vessel that either might touch. To remove it, the pair were required first to sit down before a censer of burning incense, and then to wash themselves thoroughly. Thus only could they re-enter into the state of legal cleanness. A similar impurity attached to those who came into contact with a human corpse. The Babylonians are remarkable for the extent to which they affected symbolism in religion. In the first place they attached to each god a special mystic number, which is used as his emblem and may even stand for his name in an inscription. To the gods of the First Triad-Ami, Bel, and Hea or Hoa—were assigned respectively the numbers 60, 50, and 40; to those of the Second Triad—the Moon, the Sun and the Atmosphere—were given the other integers, 30, 20, and 10 (or perhaps six). To Beltis was attached the number 15, to Nergal 12, to Bar or Nin (apparently) 40, as to Hoa; but this is perhaps doubtful. It is probable that every god, or at any rate all the principle deities, had in a similar way some numerical emblem. Many of these are, however, as yet undiscovered.

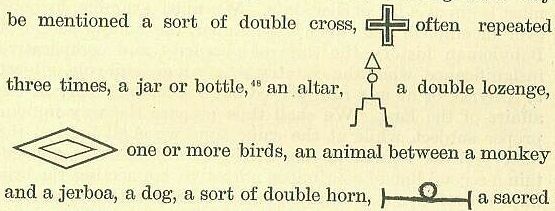

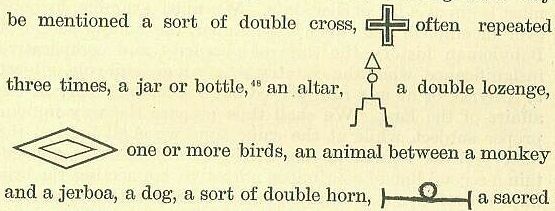

Further, each god seems to have had one or more emblematic signs by which he could be pictorially symbolized. The cylinders are full of such forms, which are often crowded into every vacant space where room could be found for them. A certain number can be assigned definitely to particular divinities. Thus a circle, plain or crossed, designates the Sun-god, San or Shamas; a six-rayed or eight-rayed star the Sun-goddess, Gula or Anunit; a double or triple thunderbolt the Atmospheric god, Vul; a serpent probably Hoa; a naked female form Nana or Ishtar; a fish Bar or Nin-ip. But besides these assignable symbols, there are a vast number with regard to which we are still wholly in the dark. Among these may

tree, an ox, a bee, a spearhead. A study of the inscribed cylinders shows these emblems to have no reference to the god or goddess named in the inscription upon them. Each, apparently, represents a distinct deity; and the object of placing them upon a cylinder is to imply the devotion of the man whose seal it is to other deities besides those whose special servant he considers himself. A single cylinder sometimes contains as many as eight or ten such emblems. The principal temples of the gods had special sacred appellations. The great temple of Bel at Babylon was known as Bit-Saggath, that of the same god at Niffer as Kharris-Nipra. that of Beltis at Warka (Erech) as Bit-Ana, that of the sun at Sippara as Bit-Parra, that of Anunit at the same place as Bit-Ulmis, that of Nebo at Borsippa as Bit-Tsida, etc. It is seldom that these names admit of explanation. They had come down apparently from the old Chaldaean times, and belonged to the ancient (Turanian) form of speech; which is still almost unintelligible. The Babylonians themselves probably in few cases understood their meaning. They used the words simply as proper names, without regarding them as significative.