Reign of Isdigerd II. His War with Rome. His Nine Years' War with the Ephthalites. His Policy towards Armenia. His Second Ephthalite War. His Character. His Coins.

The successor of Varahan V. was his son, Isdigerd the Second, who ascended the Persian throne without opposition in the year A.D. 440. His first act was to declare war against Rome. The Roman forces were, it would seem, concentrated in the vicinity of Nisibis; and Isdigerd may have feared that they would make an attack upon the place. He therefore anticipated them, and invaded the empire with an army composed in part of his own subjects, but in part also of troops from the surrounding nations. Saracens, Tzani, Isaurians, and Huns (Ephthalites?) served under his standard; and a sudden incursion was made into the Roman territory, for which the imperial officers were wholly unprepared. A considerable impression would probably have been produced, had not the weather proved exceedingly unpropitious. Storms of rain and hail hindered the advance of the Persian troops, and allowed the Roman generals a breathing space, during which they collected an army. But the Emperor Theodosius was anxious that the flames of war should not be relighted in this quarter; and his instructions to the prefect of the East, the Count Anatolius, were such as speedily led to the conclusion, first of a truce for a year, and then of a lasting treaty. Anatolius repaired as ambassador to the Persian camp, on foot and alone, so as to place himself completely in Isdigerd's power—an act which so impressed the latter that (we are told) he at once agreed to make peace on the terms which Anatolius suggested. The exact nature of these terms is not recorded; but they contained at least one unusual condition. The Romans and Persians agreed that neither party should construct any new fortified post in the vicinity of the other's territory—a loose phrase which was likely to be variously interpreted, and might easily lead to serious complications.

It is difficult to understand this sudden conclusion of peace by a young prince, evidently anxious to reap laurels, who in the first year of his reign had, at the head of a large army, invaded the dominions of a neighbor. The Roman account, that he invaded, that he was practically unopposed, and that then, out of politeness towards the prefect of the East, he voluntarily retired within his own frontier, "having done nothing disagreeable," is as improbable a narrative as we often meet with, even in the pages of the Byzantine historians. Something has evidently been kept back. If Isdigerd returned, as Procopius declares, without effecting anything, he must have been recalled by the occurrence of troubles in some other part of his empire. But it is, perhaps, as likely that he retired, simply because he had effected the object with which he engaged in the war. It was a constant practice of the Romans to advance their frontier by building strong towns on or near a debatable border, which attracted to them the submission of the neighboring district. The recent building of Theodosiopolis in the eastern part of Roman Armenia had been an instance of this practice. It was perhaps being pursued elsewhere along the Persian border, and the invasion of Isdigerd may have been intended to check it. If so, the proviso of the treaty recorded by Procopius would have afforded him the security which he required, and have rendered it unnecessary for him to continue the war any longer.

His arms shortly afterwards found employment in another quarter. The Tatars of the Transoxianian regions were once more troublesome; and in order to check or prevent the incursions which they were always ready to make, if they were unmolested, Isdigerd undertook a long war on his northeastern frontier, which he conducted with a resolution and perseverance not very common in the East. Leaving his vizier, Mihr-Narses, to represent him at the seat of government, he transferred his own residence to Nishapm, in the mountain region between the Persian and Kharesmian deserts, and from that convenient post of observation directed the military operations against his active enemies, making a campaign against them regularly every year from A.D. 443 to 451. In the year last mentioned he crossed the Oxus, and, attacking the Ephthalites in their own territory, obtained a complete success, driving the monarch from the cultivated portion of the country, and forcing him to take refuge in the desert. So complete was his victory that he seems to have been satisfied with the result, and, regarding the war as terminated, to have thought the time was come for taking in hand an arduous task, long contemplated, but not hitherto actually attempted.

This was no less a matter than the forcible conversion of Armenia to the faith of Zoroaster. It has been already noted that the religious differences which—from the time when the Armenians, anticipating Constantine, adopted as the religion of their state and nation the Christian faith (ab. A.D. 300)—separated the Armenians from the Persians, were a cause of weakness to the latter, more especially in their contests with Rome. Armenia was always, naturally, upon the Roman side, since a religious sympathy united it with the the court of Constantinople, and an exactly opposite feeling tended to detach it from the court of Ctesiphon. The alienation would have been, comparatively speaking, unimportant, after the division of Armenia between the two powers, had that division been regarded by either party as final, or as precluding the formation of designs upon the territory which each had agreed should be held by the other. But there never yet had been a time when such designs had ceased to be entertained; and in the war which Isdigerd had waged with Theodosius at the beginning of his reign, Roman intrigues in Persarmenia had forced him to send an army into that country. The Persians felt, and felt with reason, that so long as Armenia remained Christian and Persia held to the faith of Zoroaster, the relations of the two countries could never be really friendly; Persia would always have a traitor in her own camp; and in any time of difficulty—especially in any difficulty with Rome—might look to see this portion of her territory go over to the enemy. We cannot be surprised if Persian statesmen were anxious to terminate so unsatisfactory a state of things, and cast about for a means whereby Armenia might be won over, and made a real friend instead of a concealed enemy.

The means which suggested itself to Isdigerd as the simplest and most natural was, as above observed, the conversion of the Armenians to the Zoroastrian religion. In the early part of his reign he entertained a hope of effecting his purpose by persuasion, and sent his vizier, Mihr-Narses, into the country, with orders to use all possible peaceful means—gifts, blandishments, promises, threats, removal of malignant chiefs—to induce Armenia to consent to a change of religion. Mihr-Narses did his best, but failed signally. He carried off the chiefs of the Christian party, not only from Armenia, but from Iberia and Albania, telling them that Isdigerd required their services against the Tatars, and forced them with their followers to take part in the Eastern war. He committed Armenia to the care of the Margrave, Vasag, a native prince who was well inclined to the Persian cause, and gave him instructions to bring about the change of religion by a policy of conciliation. But the Armenians were obstinate. Neither threats, nor promises, nor persuasions had any effect. It was in vain that a manifesto was issued, painting the religion of Zoroaster in the brightest colors, and requiring all persons to conform to it. It was to no purpose that arrests were made, and punishments threatened. The Armenians declined to yield either to argument or to menace; and no progress at all was made in the direction of the desired conversion.

In the year A.D. 450, the patriarch Joseph, by the general desire of the Armenians, held a great assembly, at which it was carried by acclamation that the Armenians were Christians, and would continue such, whatever it might cost them. If it was hoped by this to induce Isdigerd to lay aside his proselytizing schemes, the hope was a delusion. Isdigerd retaliated by summoning to his presence the principal chiefs, viz., Vasag, the Margrave; the Sparapet, or commander-in-chief, Vartan, the Mamigonian; Vazten, prince of Iberia; Vatche, king of Albania, etc.; and having got them into his power, threatened them with immediate death, unless they at once renounced Christianity and made profession of Zoroastrianism. The chiefs, not having the spirit of martyrs, unhappily yielded, and declared themselves converts; whereupon Isdigerd sent them back to their respective countries, with orders to force everywhere on their fellow-countrymen a similar change of religion.

Upon this, the Armenians and Iberians broke out in open revolt. Vartan, the Mamigonian, repenting of his weakness, abjured his new creed, resumed the profession of Christianity, and made his peace with Joseph, the patriarch. He then called the people to arms, and in a short time collected a force of a hundred thousand men. Three armies were formed, to act separately under different generals. One watched Azerbijan, or Media Atropatene, whence it was expected that their main attack would be made by the Persians; another, under Vartan, proceeded to the relief of Albania, where proceedings were going on similar to those which had driven Armenia into rebellion; the third, under Vasag, occupied a central position in Armenia, and was intended to move wherever danger should threaten. An attempt was at the same time made to induce the Roman emperor, Marcian, to espouse the cause of the rebels, and send troops to their assistance; but this attempt was unsuccessful. Marcian had but recently ascended the throne, and was, perhaps, scarcely fixed in his seat. He was advanced in years, and naturally unenterprising. Moreover, the position of affairs in Western Europe was such that Marcian might expect at any moment to be attacked by an overwhelming force of northern barbarians, cruel, warlike, and unsparing. Attila was in A.D. 451 at the height of his power; he had not yet been worsted at Chalons; and the terrible Huns, whom he led, might in a few months destroy the Western, and be ready to fall upon the Eastern empire. Armenia, consequently, was left to her own resources, and had to combat the Persians single-handed. Even so, she might probably have succeeded, have maintained her Christianity, or even recovered her independence, had her people been of one mind, and had no defection from the national cause manifested itself. But Vasag, the Marzpan, had always been half-hearted in the quarrel; and, now that the crisis was come, he determined on going wholly over to the Persians. He was able to carry with him the army which he commanded; and thus Armenia was divided against itself; and the chance of victory was well-nigh lost before the struggle had begun. When the Persians took the field they found half Armenia ranged upon their side; and, though a long and bloody contest followed, the end was certain from the beginning. After much desultory warfare, a great battle was fought in the sixteenth year of Isdigerd (A.D. 455 or 456) between the Christian Armenians on the one side, and the Persians, with their Armenian abettors, on the other. The Persians were victorious; Vartan, and his brother, Hemaiiag, were among the slain; and the patriotic party found that no further resistance was possible. The patriarch, Joseph, and the other bishops, were seized, carried off to Persia, and martyred. Zoroastrianism was enforced upon the Armenian nation. All accepted it, except a few, who either took refuge in the dominions of Rome, or fled to the mountain fastnesses of Kurdistan.

The resistance of Armenia was scarcely overborne, when war once more broke out in the East, and Isdigerd was forced to turn his attention to the defence of his frontier against the aggressive Ephthalites, who, after remaining quiet for three or four years, had again flown to arms, had crossed the Oxus, and invaded Khorassan in force. On his first advance the Persian monarch was so far successful that the invading hordes seems to have retired, and left Persia to itself; but when Isdigerd, having resolved to retaliate, led his own forces into the Ephthalite country, they took heart, resisted him, and, having tempted him into an ambuscade, succeeded in inflicting upon him a severe defeat. Isdigerd was forced to retire hastily within his own borders, and to leave the honors of victory to his assailants, whose triumph must have encouraged them to continue year after year their destructive inroads into the north-eastern provinces of the empire.

It was not long after the defeat which he suffered in this quarter that Isdigerd's reign came to an end. He died A.D. 457, after having held the throne for seventeen or (according to some) for nineteen years. He was a prince of considerable ability, determination, and courage. That his subjects called him "the Clement" is at first sight surprising, since clemency is certainly not the virtue that any modern writer would think of associating with his name. But we may assume from the application of the term that, where religious considerations did not come into play, he was fair and equitable, mild-tempered, and disinclined to harsh punishments. Unfortunately, experience tells us that natural mildness is no security against the acceptance of a bigot's creed; and, when a policy of persecution has once been adopted, a Trajan or a Valerian will be as unsparing as a Maximin or a Galerius. Isdigerd was a bitter and successful persecutor of Christianity, which he—for a time at any rate—stamped out, both from his own proper dominions, and from the newly-acquired province of Armenia. He would have preferred less violent means; but, when they failed, he felt no scruples in employing the extremest and severest coercion. He was determined on uniformity; and uniformity he secured, but at the cost of crushing a people, and so alienating them as to make it certain that they would, on the first convenient occasion, throw off the Persian yoke altogether.

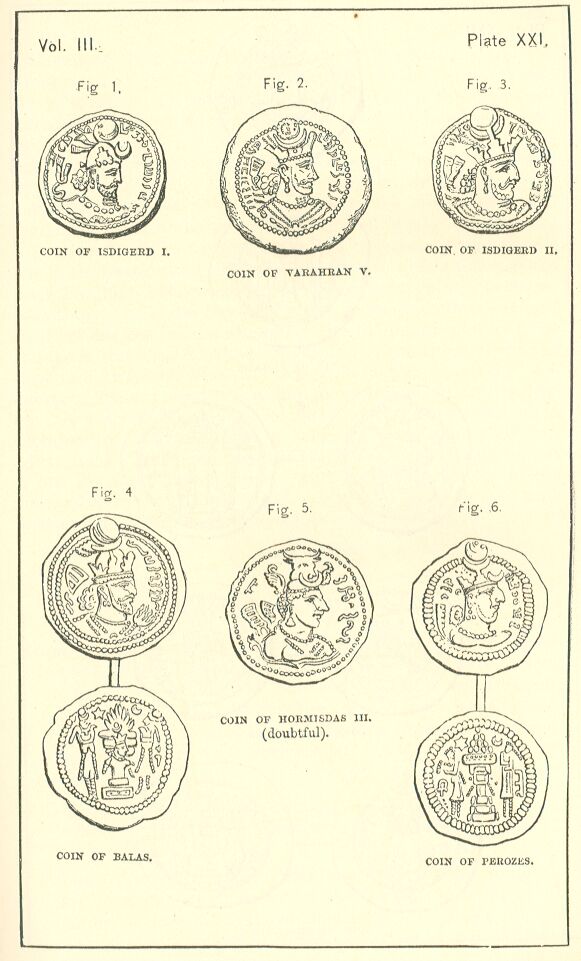

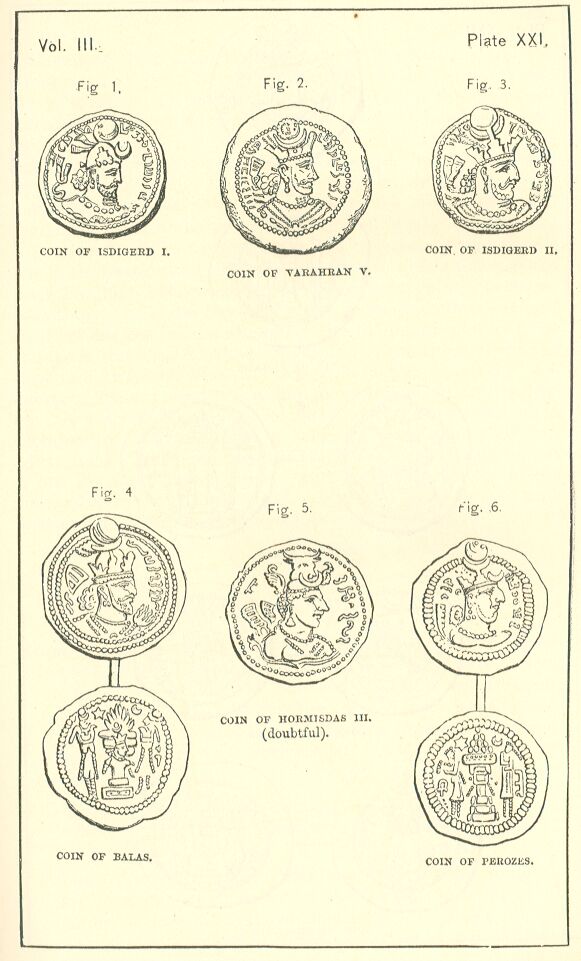

The coins of Isdigerd II. nearly resemble those of his father, Varahran V., differing only in the legend, and in the fact that the mural crown of Isdigerd is complete. The legend is remarkably short, being either Masdisn kadi Tezdikerti, or merely Kadi Yezdikerti—i.e. "the Ormazd-worshipping great Isdigerd;" or "Isdigord the Great." The coins are not very numerous, and have three mint-marks only, which are interpreted to mean "Khuzistan," "Ctesiphon," and "Nehavend." [PLATE XXI., Fig. 3.]