Accession of Hormisdas IV. His good Government in the Earlier Portion of his Reign. Invasion of Persia by the Romans under Maurice. Defeats of Adarman and Tamchosro. Campaign of Johannes. Campaigns of Philippicus and Heraclius. Tyranny of Hormisdas. He is attacked by the Arabs, Khazars, and Turks. Bahram defeats the Turks. His Attack on Lazica. He suffers a Defeat. Disgrace of Bahram. Dethronement of Hormisdas IV. and Elevation of Chosroes II. Character of Hormisdas. Coins of Hormisdas.

At the death of Chosroes the crown was assumed without dispute or difficulty by his son, Hormazd, who is known to the Greek and Latin writers as Hormisdas IV. Hormazd was the eldest, or perhaps the only, son borne to Chosroes by the Turkish princess, Fakim, who, from the time of her marriage, had held the place of sultana, or principal wife. His illustrious descent on both sides, added to the express appointment of his father, caused him to be universally accepted as king; and we do not hear that even his half-brothers, several of whom were older than himself, put forward any claims in opposition to his, or caused him any anxiety or trouble. He commenced his reign amid the universal plaudits and acclamations of his subjects, whom he delighted by declaring that he would follow in all things the steps of his father, whose wisdom so much exceeded his own, would pursue his policy, maintain his officers in power, and endeavor in all respects to govern as he had governed. When the mobeds attempted to persuade him to confine his favor to Zoroastrians and persecute such of his subjects as were Jews or Christians he rejected their advice with the remark that, as in an extensive territory there were sure to be varieties of soil, so it was fitting that a great empire should embrace men of various opinions and manners. In his progresses from one part of his empire to another he allowed of no injury being done to the lands or gardens along the route, and punished severely all who infringed his orders. According to some, his good dispositions lasted only during the time that he enjoyed the counsel and support of Abu-zurd-mihir, one of the best advisers of his father; but when this venerated sage was compelled by the infirmities of age to quit his court he fell under other influences, and soon degenerated into the cruel tyrant which, according to all the authorities, he showed himself in his later years.

Meanwhile, however, he was engaged in important wars, particularly with the Roman emperors Tiberius and Maurice, who, now that the great Chosroes was dead, pressed upon Persia with augmented force, in the confident hope of recovering their lost laurels. On the first intelligence of the great king's death, Tiberius had endeavored to negotiate a peace with his successor, and had offered to relinquish all claim on Armenia, and to exchange Arzanene with its strong fortress, Aphumon, for Daras; but Hormisdas had absolutely rejected his proposals, declared that he would surrender nothing, and declined to make peace on any other terms than the resumption by Rome of her old system of paying an annual subsidy. The war consequently continued; and Maurice, who still held the command, proceeded, in the summer of A.D. 579, to take the offensive and invade the Persian territory. He sent a force across the Tigris under Romanus, Theodoric, and Martin, which ravaged Kurdistan, and perhaps penetrated into Media, nowhere encountering any large body of the enemy, but carrying all before them and destroying the harvest at their pleasure. In the next year, A.D. 580, he formed a more ambitious project. Having gained over, as he thought, Alamundarus, the leader of the Saracens dependent on Persia, and collected a fleet to carry his stores, he marched from Gircesium down the course of the Euphrates, intending to carry the war into Southern Mesopotamia, and perhaps hoping to capture Ctesiphon. He expected to take the Persians unawares, and may not unnaturally have looked to gain an important success; but, unhappily for his plans, Alamundarus proved treacherous. The Persian king was informed of his enemy's march, and steps were at once taken to render it abortive. Adarman was sent, at the head of a large army, into Roman Mesopotamia, where he threatened the important city of Callinicus in Maurice's rear. That general dared advance no further. On the contrary, he felt constrained to fall back, to give up his scheme, burn his fleet, and return hastily within the Roman frontier. On his arrival, he engaged Adarman near the city which he was attacking, defeated him, and drove him back into Persia.

In the ensuing spring, after another vain attempt at negotiation, the offensive was taken by the Persians, who, early in A.D. 581, crossed the frontier under Tam-chosro, and attacked the Roman city of Constantia, or Constantina. Maurice hastened to its relief; and a great battle was fought in the immediate vicinity of the city, wherein the Persians were completely defeated, and their commander lost his life. Further advantages might have been gained; but the prospect of the succession drew Maurice to Constantinople, where Tiberius, stricken with a mortal disease, received him with open arms, gave his daughter and the state into his care, and, dying soon after, left him the legacy of the empire, which he administered with success for above twenty years.

On quitting the East, Maurice devolved his command upon an officer who bore the very common name of Johannes, but was distinguished further by the epithet of Mustacon, on account of his abundant moustache. This seems to have been a bad appointment. Mustacon was unequal to the position. He gave the Persians battle at the conjunction of the Nymphius with the Tigris, but was defeated with considerable loss, partly through the misconduct of one of his captains. He then laid siege to Arbas, a strong fort on the Persian side of the Nymphius, while the main body of the Persians were attacking Aphumon in the neighboring district of Arzanene. The garrison of Arbas made signals of distress, which speedily brought the Persian army to their aid; a second battle was fought at Arbas, and Mustacon was again defeated, and forced to retire across the Nymphius into Roman territory. His incapacity was now rendered so clearly evident that Maurice recalled him, and gave the command of the army of the East to a new general, Philippicus, his brother-in-law.

The first and second campaigns of Philippicus, in the years A.D. 584 and 585, were of the most commonplace character. He avoided any general engagement, and contended himself with plundering inroads into the Persian territory on either side of the Upper Tigris, occasionally suffering considerably from want of water and provisions. The Persians on their part undertook no operations of importance until late in A.D. 585, when Philippicus had fallen sick. They then made attempts upon Monocartum and Martyropolis, which were unsuccessful, resulting only in the burning of a church and a monastery near the latter town. Neither side seemed capable of making any serious impression upon the other; and early the next year negotiations were resumed, which, however, resulted in nothing.

In his third campaign Philippicus adopted a bolder line of proceeding. Commencing by an invasion of Eastern Mesopotamia, he met and defeated the Persians in a great battle near Solachon, having first roused the enthusiasm of his troops by carrying along their ranks a miraculous picture of our Lord, which no human hand had painted. Hanging on the rear of the fugitives, he pursued them to Daras, which declined to receive within its walls an army that had so disgraced itself. The Persian commander withdrew his troops further inland; and Philippicus, believing that he had now no enemy to fear, proceeded to invade Arzanene, to besiege the stronghold of Chlomaron, and at the same time to throw forward troops into the more eastern parts of the country. He expected them to be unopposed; but the Persian general, having rallied his force and augmented it by fresh recruits, had returned towards the frontier, and, hearing of the danger of Arzanene, had flown to its defence. Philippicus was taken by surprise, compelled to raise the siege of Chlomaron, and to fall back in disorder. The Persians pressed on his retreat, crossed the Nymphius after him, and did not desist from the pursuit until the imperial general threw himself with his shattered army into the strong fortress of Amida. Disgusted and discredited by his ill-success, Philippicus gave over the active prosecution of the war to Heraclius, and, remaining at head-quarters, contented himself with a general supervision.

Heraclius, on receiving his appointment, is said to have at once assumed the offensive, and to have led an army, consisting chiefly or entirely of infantry, into Persian territory, which devastated the country on both sides of the Tigris, and rejoined Philippicus, without having suffered any disaster, before the winter. Philippicus was encouraged by the success of his lieutenant to continue him in command for another year; but, through prudence or jealousy, he was induced to intrust a portion only of the troops to his care, while he assigned to others the supreme authority over no less than one third of the Roman army. The result was, as might have been expected, inglorious for Rome. During A.D. 587 the two divisions acted separately in different quarters; and, at the end of the year, neither could boast of any greater success than the reduction, in each case, of a single fortress. Philippicus, however, seems to have been satisfied; and at the approach of winter he withdrew from the East altogether, leaving Heraclius as his representative, and returned to Constantinople.

During the earlier portion of the year A.D. 588 the mutinous temper of the Roman army rendered it impossible that any military operations should be undertaken. Encouraged by the disorganization of their enemies, the Persians crossed the frontier, and threatened Constantina, which was however saved by Germanus. Later in the year, the mutinous spirit having been quelled, a counter-expedition was made by the Romans into Arzanene. Here the Persian general, Maruzas, met them, and drove them from the province; but, following up his success too ardently, he received a complete defeat near Martyropolis, and lost his life in the battle. His head was cut off by the civilized conquerors, and sent as a trophy to Maurice.

The campaign of A.D. 589 was opened by a brilliant stroke on the part of the Persians, who, through the treachery of a certain Sittas, a petty officer in the Roman army, made themselves masters of Martyropolis. It was in vain that Philippicus twice besieged the place; he was unable to make any impression upon it, and after a time desisted from the attempt. On the second occasion the garrison was strongly reinforced by the Persians under Mebodos and Aphraates, who, after defeating Philippicus in a pitched battle, threw a large body of troops into the town. Philippicus was upon this deprived of his office, and replaced by Comentiolus, with Heraclius as second in command. The new leaders, instead of engaging in the tedious work of a siege, determined on re-establishing the Roman prestige by a bold counter-attack. They invaded the Persian territory in force, ravaged the country about Nisibis, and brought Aphraates to a pitched battle at Sisarbanon, near that city. Victory seemed at first to incline to the Persians; Comentiolus was defeated and fled; but Horaclius restored the battle, and ended by defeating the whole Persian army, and driving it from the field, with the loss of its commander, who was slain in the thick of the fight. The next day the Persian camp was taken, and a rich booty fell into the hands of the conquerors, besides a number of standards. The remnant of the defeated army found a refuge within the walls of Nisibis. Later in the year Comentiolus recovered to some extent his tarnished laurels by the siege and capture of Arbas, whose strong situation in the immediate vicinity of Martyropolis rendered the position of the Persian garrison in that city insecure, if not absolutely untenable.

Such was the condition of affairs in the western provinces of the Persian Empire, when a sudden danger arose in the east, which had strange and most important consequences. According to the Oriental writers, Hormisdas had from a just monarch gradually become a tyrant; under the plea of protecting the poor had grievously oppressed the rich; through jealousy or fear had put to death no fewer than thirteen thousand of the upper classes, and had thus completely alienated all the more powerful part of the nation. Aware of his unpopularity, the surrounding tribes and peoples commenced a series of aggressions, plundered the frontier provinces, defeated the detachments sent against them under commanders who were disaffected, and everywhere brought the empire into the greatest danger. The Arabs crossed the Euphrates and spread themselves over Mesopotamia; the Khazars invaded Armenia and Azerbijan; rumor said that the Greek emperor had taken the field and was advancing on the side of Syria, at the head of 80,000 men; above all, it was quite certain that the Great Khan of the Turks had put his hordes in motion, had passed the Oxus with a countless host, occupied Balkh and Herat, and was threatening to penetrate into the very heart of Persia. The perilous character of the crisis is perhaps exaggerated; but there can be little doubt that the advance of the Turks constituted a real danger. Hormisdas, however, did not even now quit the capital, or adventure his own person. He selected from among his generals a certain Varahran or Bahram, a leader of great courage and experience, who had distinguished himself in the wars of Anushirwan, and, placing all the resources of the empire at his disposal, assigned to him the entire conduct of the Turkish struggle. Bahram is said to have contented himself with a small force of picked men, veterans between forty and fifty years of age, to have marched with them upon Balkh, contended with the Great Khan in several partial engagements, and at last entirely defeated him in a great battle, wherein the Khan lost his life. This victory was soon followed by another over the Khan's son, who was made prisoner and sent to Hormisdas. An enormous booty was at the same time despatched to the court; and Bahram himself was about to return, when he received his master's orders to carry his arms into another quarter.

It is supposed, by some that, while the Turkish hordes were menacing Persia upon the north-east, a Roman army, intended to act in concert with them, was sent by Maurice into Albania, which proceeded to threaten the common enemy in the north-west. But the Byzantine writers know of no alliance at this time between the Romans and Turks; nor do they tell of any offensive movement undertaken by Rome in aid of the Turkish invasion, or even simultaneously with it. According to them, the war in this quarter, which certainly broke out in A.D. 589, was provoked by Hormisdas himself, who, immediately after his Turkish victories, sent Bahram with an army to invade Colchis and Suania, or in other words to resume the Lazic war, from which Anushirwan had desisted twenty-seven years previously. Bahram found the province unguarded, and was able to ravage it at his will; but a Roman force soon gathered to its defence, and after some manoeuvres a pitched battle was fought on the Araxes, in which the Persian general suffered a defeat. The military results of the check were insignificant; but it led to an internal revolution. Hormisdas had grown jealous of his too successful lieutenant, and was glad of an opportunity to insult him. No sooner did he hear of Bahram's defeat than he sent off a messenger to the camp upon the Araxes, who deprived the general of his command, and presented to him, on the part of his master, a distaff, some cotton, and a complete set of women's garments. Stung to madness by the undeserved insult, Bahram retorted with a letter, wherein he addressed Hormisdas, not as the son, but as the daughter of Chosroes. Shortly afterwards, upon the arrival of a second messenger from the court, with orders to bring the recalcitrant commander home in chains, Bahram openly revolted, caused the envoy to be trampled upon by an elephant, and either by simply putting before the soldiers his services and his wrongs, or by misrepresenting to them the intentions of Hormisdas towards themselves, induced his whole army with one accord to embrace his cause.

The news of the great general's revolt was received with acclamations by the provinces. The army of Mesopotamia, collected at Nisibis, made common cause with that of Albania; and the united force, advancing on the capital by way of Assyria, took up a position upon the Upper Zab river. Hormisdas sent a general, Pherochanes, to meet and engage the rebels; but the emissaries of Bahram seduced his troops from their allegiance; Pherochanes was murdered; and the insurgent army, augmented by the force sent to oppose it, drew daily nearer to Ctesiphon. Meanwhile Hormisdas, distracted between hate and fear, suspecting every one, trusting no one, confined himself within the walls of the capital, where he continued to exercise the severities which had lost him the affections of his subjects. According to some, he suspected his son, Chosroes, of collusion with the enemy, and drove him into banishment, imprisoning at the same time his own brothers in-law, Bindoes and Bostam, who would be likely, he thought, to give their support to their nephew. These violent measures precipitated the evils which he feared; a general revolt broke out in the palace; Bostam and Bindoes, released from prison, put themselves at the head of the malcontents, and, rushing into the presence-chamber, dragged the tyrant from his throne, stripped him of the diadem, and committed him to the dungeon from which they had themselves escaped. The Byzantine historians believed that, after this, Hormisdas was permitted to plead his cause before an assembly of Persian nobles, to glorify his own reign, vituperate his eldest son, Chosroes, and express his willingness to abdicate in favor of another son, who had never offended him. They supposed that this ill-judged oration had sealed the fate of the youth recommended and of his mother, who were cut to pieces before the fallen monarch's eyes, while at the same time the rage of the assembly was vented in part upon Hormisdas himself, who was blinded, to make his restoration impossible. But a judicious critic will doubt the likelihood of rebels, committed as were Bindoes and Bostam, consenting to allow such an appeal as is described by Theophylact; and a perusal of the speeches assigned to the occasion will certainly not diminish his scepticism. The probability would seem to be that Hormisdas was blinded as soon as committed to prison, and that shortly afterwards he suffered the general fate of deposed sovereigns, being assassinated in his place of confinement.

The deposition of Hormisdas was followed almost immediately by the proclamation of his eldest son, Chosroes, the prince known in history as "Eberwiz" or "Parviz," the last great Persian monarch. The rebels at Ctesiphon had perhaps acted from first to last with his cognizance: at any rate, they calculated on his pardoning proceedings which had given him actual possession of a throne whereto, without their aid, he might never have succeeded. They accordingly declared him king of Persia without binding him by conditions, and without negotiating with Bahram, who was still in arms and at no great distance.

Before passing to the consideration of the eventful reign with which we shall now have to occupy ourselves, a glance at the personal character of the deceased monarch will perhaps be expected by the reader. Hormuzd is pronounced by the concurrent voice of the Greeks and the Orientals one of the worst princes that ever ruled over Persia. The fair promise of his early years was quickly clouded over; and during the greater portion of his reign he was a jealous and capricious tyrant, influenced by unworthy favorites, and stimulated to ever-increasing severities by his fears. Eminence of whatsoever kind roused his suspicions; and among his victims were included, besides the noble and the great, a large number of philosophers and men of science. His treatment of Bahram was at once a folly and a crime—an act of black ingratitude, and a rash step, whereof he had not counted the consequences. To his other vices he added those of indolence and effeminacy. From the time that he became king nothing could drag him from the soft life of the palace; in no single instance did he take the field, either against his country's enemies or his own. Miserable as was his end, we can scarcely deem him worthy of our pity, since there never lived a man whose misfortunes were more truly brought on him by his own conduct.

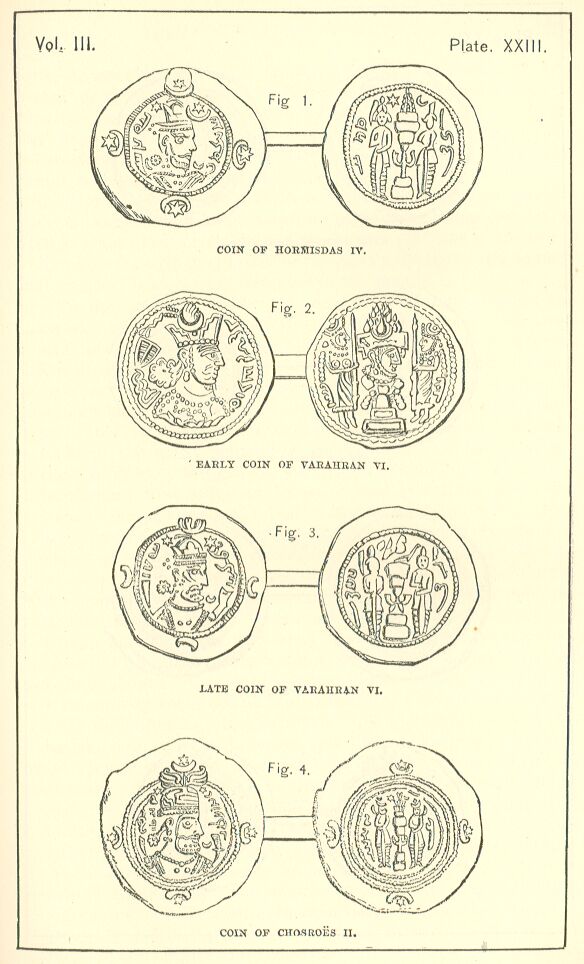

The coins of Hormisdas IV. are in no respect remarkable. The head seems modelled on that of Chosroes, his father, but is younger. The field of the coin within the border is somewhat unduly crowded with stars and crescents. Stars and crescents also occur outside the border, replacing the simple crescents of Chosroes, and reproducing the combined stars and crescents of Zamasp. The legend on the obverse is Auhramazdi afzud, or sometimes Auhramazi afzun; on the reverse are commonly found, besides the usual fire-altar and supporters, a regnal year and a mint-mark. The regnal years range from one to thirteen; the number of the mint-marks is about thirty. [PLATE XXIII., Fig. 1.]